Marching Down Freedom’s Road, Day 4

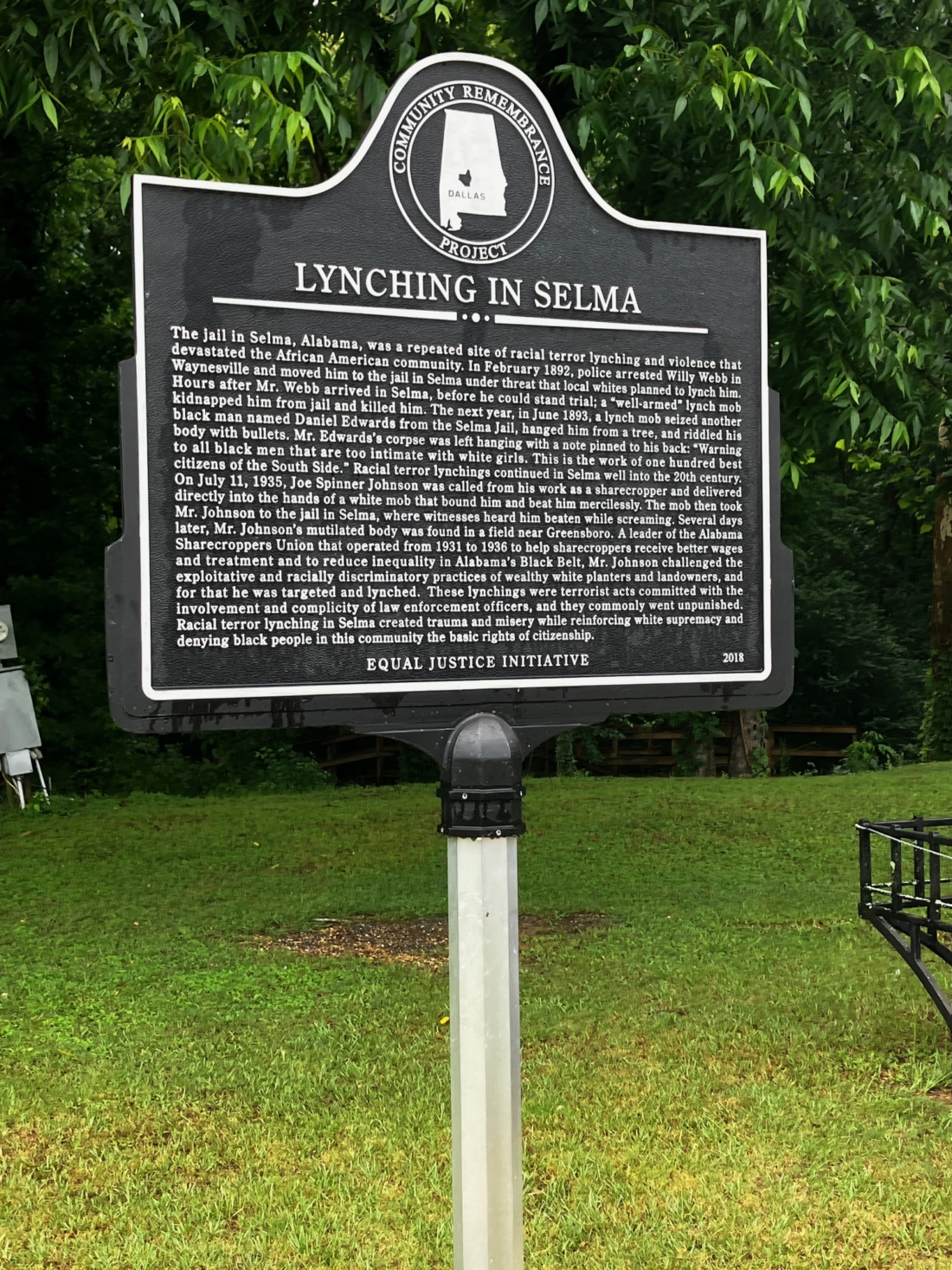

Each day we delve deeper into this history. We spent today in Selma, but on the way there, we stopped in Lowndes County, to visit the site of a Civil Rights era Tent City and learn more about the quest for voting rights.

In 1965 (and even today) Lowndes County Alabama was one of the poorest counties in America. It was 85% black in 1965, but even after the signing of the Voting Rights Act in August of that year, there was not one black registered voter nor one black elected official in Lowndes County. The symbol of the Democratic party in power throughout the state was a rooster, with the words above it, “White Supremacy.” Can you imaging a time when that was a selling point? Even if black citizens could vote, whom could they vote for besides those who had been oppressing them for generations?

Stokely Carmichael and other SNCC volunteers went door to door encouraging people to register to vote, by creating a new third party, and its symbol was a black panther. “Even those who could not read could tell the difference between a rooster and a black panther,” said one of those organizers, decades later in a documentary segment we watched.

Despite the victories of the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act, racism continued, and black citizens were punished for reaching for their newly guaranteed rights as citizens. Many were fired by white employers, and 40 families were evicted from the land they leased from white property owners, some having been there for over 50 years. While some left the state, 8 families found “refuge” in this Tent City on land owned by black farmers between Selma and Montgomery. With no running water, electricity, commerce, healthcare, or amenities, they were supported by their communities there for up to 2 years. This is a piece of history I do not remember learning about in school.

We are not “travelling chronologically,” and each day I challenge my mind to take all of the pieces of knowledge and understanding that it is challenged with, and put them into historical and moral order. So from Tent City (late 1965) we drove back in time to the early 60s, towards Selma, and stopped at the National Voting Rights Museum and Institute. You might think a place with such a high-minded name would be somewhat like what we saw in Atlanta, but it could not have been more different. There were very few artifacts, but many photos and much information gathered by the local museum creators. We were greeted by Sam Walker, who had as a child been a part of the community of marchers. He told us he was the museum’s historian, but he seemed to be one of perhaps three employees.

Small but mighty, the museum’s self-guided tour contained more history which was new to me, including that of the Courageous 8. These were eight leaders from Selma, including two women, who founded the Dallas County Voters League. It was this group, led by Amelia Boynton after her husband Sam’s death, who requested that Martin Luther King Jr. come to Selma to help them with a march for voting rights. It never would have happened had they not organized and then reached out to him.

We would learn more about this later from a highlight of the day, a talk from one of the youngest marchers, Ms. Jo Ann Bland. Like Charles Person in Atlanta, Ms. Bland relayed her experiences with power and conviction, and often her sharp wit. As a child she wasn’t sure what all the fuss was about over freedom. She knew that Abraham Lincoln had freed the slaves. Why were the grown-ups going on and on about freedom? But when her grandmother told her she could not sit on the swiveling stools and eat an ice cream at Carter’s Drug Store like the white children, but if this fight for freedom was won, she would be able to, she was ready to sign up! She went to her first SNCC meeting with her older brothers when she was eight and went on her first march, was arrested and went to jail, at age 11.

She said that King’s acceptance of the invitation to Selma brought the “three M’s” to their effort: Money, Motivation, and Media. She remembered being in the middle of the 600 people marching 2 by 2 on Bloody Sunday, and how it “became very real very fast.” John Lewis and Hosea Williams, at the head of the line, were refused passage by the armed and mounted troopers at the foot of the Edmund Pettus Bridge, and told they had two minutes to disperse the marchers. “In 15 seconds, they attacked them.” They attacked with batons and tear gas, essentially launching a lopsided battle with American citizens, using chemical warfare.

After hearing her story, and her thoughts on racism today, we had a chance to walk across the bridge ourselves. As I crested it, I imagined what those marchers might have thought 58 years ago when the state-sponsored army set to attack them came into view.

We gathered for a makeshift service at a Memorial Park at the foot of the bridge, where we lit candies, offered prayers, and said the mourners Kaddish. I did this last year on a trip to Poland, saying Kaddish before mass graves and at Auschwitz. Then I was saying the memorial prayer for mostly Jewish dead. Here, while some of the martyrs were Jewish, most were not, and most were African American. Why say Kaddish?

Just as in Judaism we say prayers for martyrs of our people, those who lost their lives fighting for civil rights for African Americans were indeed martyrs of their people. And aren’t we all ONE people? Somehow saying Kaddish seemed appropriate in that moment, for Jimmy Lee Jackson, James Reeb, and Jo Ann’s mother, who died because the hospital had to wait for “black blood” to arrive on a bus from Jackson when she needed a transfusion to save her and her unborn child. By the time it arrived, three-year-old Jo Ann’s mother and her unborn brother were gone, and her Detroit grandmother had come back after 35 years of (more) freedom to raise her.

We ended our “service” singing We Shall Overcome. I am quite sure we did not sound as good as the marchers did as they bolstered themselves with that song, but it was a powerful moment of bringing the past into the present.

Onward.